Storytelling at Forest Days and Beyond

During this time of uncertainty and change, we can tell each other stories. These stories might come through facebook or facetime, zoom meetings, or across a six foot driveway divide, or they may happen in your own homes with your families around the dinner table, or out on the trail while hiking. Storytelling could become a legitimate part of your schooling at home experience. Storytelling could become a way for us to entertain ourselves, distract ourselves, and comfort each other. Storytelling has been a part of human culture for millenia, and we all have ancestral connections to this practice, if not current ones!

In this blog post I am going to share some storytelling stories from Blue Hill Heritage Trust’s Forest Day program (which is cancelled while schools are closed). I am also going to reflect on why storytelling is important in the programming we do and offer some tips for trying it yourself with the children in your life.

At Surry Elementary School Forest Days we often start our session sitting on logs in a circle under the high boughs of a very old Red Oak Tree on the banks of Patten Stream. When kindergarten and first graders are excited to be outdoors, excited to return to the fort they were building, or the game they were playing, it is hard to get their attention during the opening circle. I have found, however, that telling a story quiets the boisterousness for a few precious moments and in these moments, as the imagination is stirred, so much takes place. They learn about natural phenomenon, cultivate a sense of place, get introductions to practical skills, learn ways of stewardship, collectively celebrate the place we live in, and gain inspiration for play and explorations later on.

At Surry Elementary School Forest Days we often start our session sitting on logs in a circle under the high boughs of a very old Red Oak Tree on the banks of Patten Stream. When kindergarten and first graders are excited to be outdoors, excited to return to the fort they were building, or the game they were playing, it is hard to get their attention during the opening circle. I have found, however, that telling a story quiets the boisterousness for a few precious moments and in these moments, as the imagination is stirred, so much takes place. They learn about natural phenomenon, cultivate a sense of place, get introductions to practical skills, learn ways of stewardship, collectively celebrate the place we live in, and gain inspiration for play and explorations later on.

Where do I find the stories, you might ask? Sometimes I adapt stories from ones I have heard other storytellers tell, sometimes I remember a story from my childhood and revive it for a current context. Sometimes I tell stories that really happened – the time my sister raised pet worms or the time a black bear came up to our front door, or the time my friends settled an argument with a ruffed grouse feather. Sometimes stories arise from watching students play and explore and noticing their passions and interests – like the time we had a hollow tree at our program site which inspired games about snakes (and stories too). Stories come from the land more often than not. They spring from the geography, the local species, the weather, the ecological connections happening in a place. And the people. The people of the past, the present and the future. What happened here? What is happening here? What should happen here? (1) is a framework I try to hold in mind when thinking of a story to tell.

We all have stories we tell everyday in different ways. You don’t need to be an expert storyteller to share! I certainly am not. And yet, a classroom full of kindergarteners will listen quite quietly. There is something visceral and appealing about stories.

We are surrounded by stories everyday – they are myriad in the landscape, unfolding at both slow and rapid paces – stories of alewives swimming upstream over waterfalls and fish ladders, eagles waiting on the rocks looking for silver flashing bellies in the sun, the fish, moving as fast as they can to spawn in the ponds. Or slower stories like those in the hard brown winter buds that the children think are dead and gone, where growing and greening happens for months and unfurling into sun-catching, breathing, beautiful foliage, takes time and patience. Stories can contain facts and information, but they hold more than that, they capture the magic of life moving and changing all around us, some of which is not explainable, only felt in the connections and networks of all that the story reveals.

Why Tell Stories?

Stories can help us in building a sense of place, a perception, a feeling, a knowledge of place. In order for stories to be authentic to the season, to the needs/interests of the group, and to the actual place we go to during our Forest Days program, I often make them up or at the very least adapt them from other stories. Part of the fun of oral storytelling is that you can tweak whatever you want! If the original story describes a rainy day, but you are experiencing a windy day, you can adjust to make the story’s details really place-based and tune participants into what is happening in the moment around them, if they haven’t already noticed. This is a technique to not only promote greater understanding of local weather conditions, for example, but also encourage a connection to place through the senses and a grounding mindfulness to the present time. The characters in the stories I tell at Patten Stream are often beaver, crow, turkey, chipmunk, cottontail rabbit, red squirrel, white-tailed deer, young spruce, and grandmother oak – all animals and trees that we have seen directly or through other signs like dwellings, tracks, nibbled branches.

Stories can be a way to manage a group and create a calm space during an opening circle without shouting and demanding attention in the usual ways. The sound of a story gradually lulls a rowdy bunch and before long all ears are listening, all brains are active, all imaginations working. Community building and learning can happen subtly and easily in the context of a story.

Stories are a teaching/learning tool, an alternative way to share information about the natural world and our interactions with it and each other. Everything from the four directions, to seasonal camouflage, to bird species and song, to fire building skills, to weather patterns, to animal behavior and food sources, to group agreements, to care for the natural world, to social-emotional cues, to technical science terms, phenology, and more can be introduced through stories, often with fictional scenarios as well as factual ones.

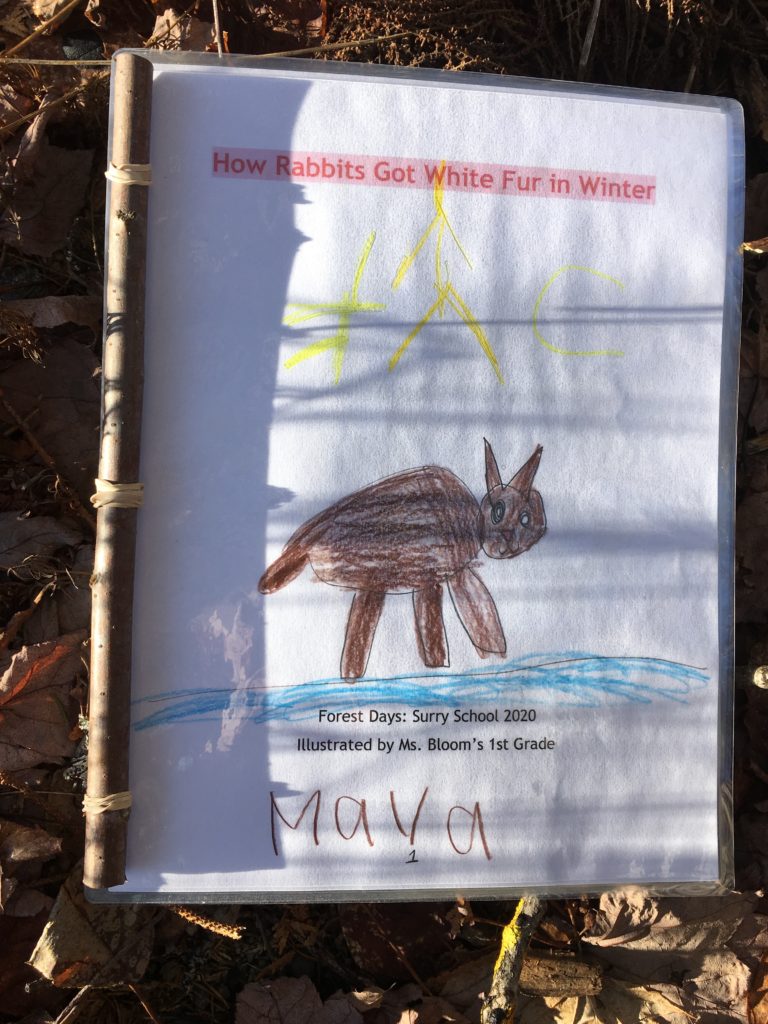

Storytelling can strengthen the imagination as the listener(s) have to conjure up their own images to match the words and this takes concentration, focus, and deep engagement. As a test one time I asked the first graders I was working with to retell a story, How Rabbits Got White Fur in Winter to me several weeks after I had first told it to them. They were able to recall almost every detail of the story, in chronological order. Maybe it was because there was a beaver holding a magic birch staff under a full moon. Or maybe it was because a father rabbit desperately needing to find food for his children on a cold winter night meets a golden crowned kinglet freezing in the path and gives her some of his fur for warmth, taking it right out of his hide. Either way these students now know that golden crowned kinglets, the smallest bird of the northern forest, are connected in a very real way with the snowshoe hare as the story ends thus: “This is how rabbits came to have white fur in the winter. And now, every spring, they shed their winter coat and grow back their brown fur for the summer, and the golden crowned kinglets use the white fur that has been shed to line their nests so that their eggs stay warm until they hatch.” A potentially complicated ecological relationship is now vivid in their minds. To read this story, click HERE.

A Story:

The last story I told the Surry Kindergarten before schools closed from covid 19 was one that I made up in honor of the changing seasons called, Penelope the Porcupine Goes Looking For Spring. You can access the written version HERE. But bear in mind that this is a story to be told and does not have any illustrations unless you create them yourself, of course, which students like to do occasionally at Forest Days.

This story has lots of natural history knowledge, advice about learning to cope with emotions, and a little bit of magic too. To read about more curricular connections click HERE.

Beginning of the story:

ONE MORNING young Penelope the Porcupine decided to pay her friend Punk the Skunk a visit. She was feeling blue from the long cold winter and was sad that all the trees still looked so dead. She really should have stayed home to clean her house, but she decided to put it off for another day. Did you know that porcupines poop a lot? They poop so much that sometimes they have to find a new home! Penelope had reached the stage where she either needed to clean or move out…

End of the story:

“Break a branch from the bush outside the cave and you will find spring,” said Wise Mother Bat. Penelope wasn’t convinced but she did as she was told, and when she held the broken branch in her paw and looked very closely she saw bright green hiding under the bark. When she opened the hard brown bud she found tiny folded green leaves!

“Spring is always with us if we know where to look. It is never fully gone even in the depths of the coldest winter. Just know that each plant in the forest, however dead it may look now, holds new life that will come forth when the sun shines high in the sky.”

Penelope smiled and held the branch close. Then she decided to collect some of the branches with the secret green inside of them and bring them home with her to be a reminder that spring is never far away.”

After telling this story, the kindergarteners were fascinated with detecting whether a branch was alive or not, scraping their fingernails along a small section of the thin bark to see whether or not it was green underneath. Seeing the green under brown dead-looking bark was exciting for them and they would call out to each other, “look! It’s some of the secret green!” A direct quote from the story. Now when a child is bending or breaking a branch to use for their fort or a woodland craft, they have a method of checking in with the tree to see if it is alive at a time of year when it is hard to tell. We also look for buds at the tips of branches as another sign of life.

Now You Try!

- Go outside and spend some time. Observe, sense, feel. Inevitably there will be something you noticed that you are excited to share with someone else! This is the beginning of a story from the land.

- After you and/or your children have been outside playing, ask them to share their “story of the day” – a practice that is common in Jon Young’s teachings and in his book Coyote’s Guide to Connecting with Nature.

- During a hike you could stop on the trail and sit awhile on a warm rock and share your “nature notes” with each other.

- If you find animal tracks in the snow or in the mud, come up with a story about what that animal was doing and where they were going.

- Ask your children to bring a natural treasure to an outdoor gathering space or indoors to do a “show and tell.”

By Landere Naisbitt, Outreach Coordinator

- Greenwood, D. A. (2014). A critical theory of place-conscious education. In AERA Handbook on Environmental Education Research. New York: Lawrence-Erlbaum.